Editorial for COCI '21 Contest 1 #5 Volontiranje

Submitting an official solution before solving the problem yourself is a bannable offence.

We use 'LIS' as a shorthand for a longest increasing subsequence.

The first subtask can be solved by finding every LIS, and then find via dynamic programming with bitmasks a set of them which do not overlap.

For the rest of the subtasks, some more insight into the structure of the longest increasing subsequences is needed. The solution in short is the following: we can remove the subsequences one by one, each time greedily building the lexicographically smallest LIS. A naive implementation of that would be too slow, so it is necessary to do some backtracking and removing of certain elements for which we are sure that they will not help with the solution, so that the time complexity gets reduced.

A more detailed description and proofs of the observations are given, but first we will mention a couple of general properties of this type of configuration, which are common in these types of tasks.

For each index

, let's define

as the length of the longest increasing subsequence ending at index

. This can be calculated with the formula

using standard algorithms for finding a LIS. Furthermore, let

denote the length of a LIS, i.e.

. Also, for a fixed positive integer

, let's define

to be the set of all indices

for which

. Two important observations are:

Claim

For all positive integers, if we look at the values corresponding to the indices of

, they will be decreasing.

Proof

If there weresuch that

and

, the longest increasing subsequence ending at

could be extended to

and then

. □

Claim

For each LIS(where

), it holds that

for all

. In other words, if we look at a fixed index

, it will always find itself at the same position in every LIS (precisely at position

).

Proof

Just as in the previous claim, we conclude that. Noting that

and

, these

numbers must be exactly

. □

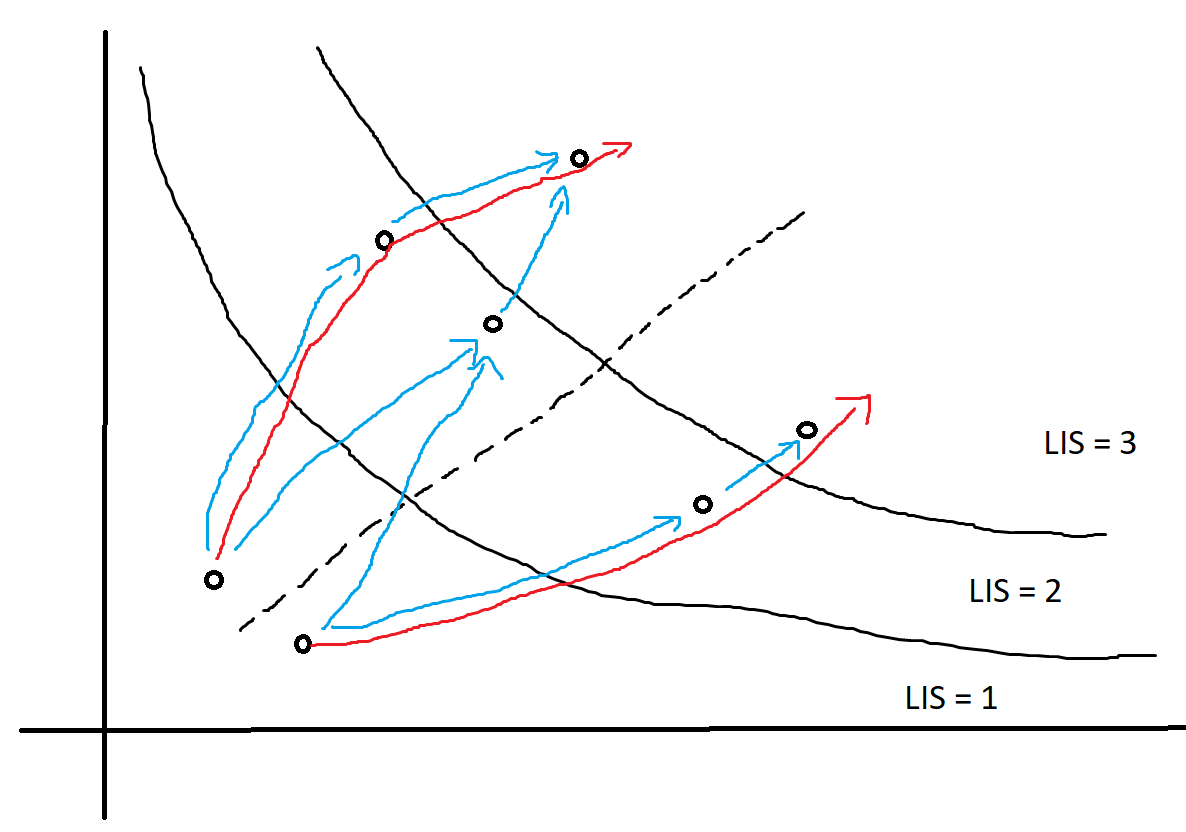

The things mentioned so far can be visualized in the following way (see image below): the given permutation can be interpreted as a set of points in coordinate plane, and increasing subsequences can be thought of as path going through the points, moving 'up and to the right'. Having in mind the claims mentioned above, the sets

come in layers, and a LIS (red arrows) pass through one point in each layer.

Between every two neighbouring layers, blue edges are drawn between pairs of points where an increasing subsequence of the first point can be extended to the second point (those are actually pairs of points where the second point is 'up and to the right' of the first point). Thus, a LIS is any path using the blue edges which starts in the first layer and ends in the last layer. Also, for each point, all of its neighbours form a segment of points in the next layer.

Now we will mention the claims specific to the problem.

Claim 1:

Assume that in the optimal solution, the number of LIS's is equal to , and that the indices of the

LIS are denoted by

. Then, there exists an optimal solution such that for each

, it holds that

.

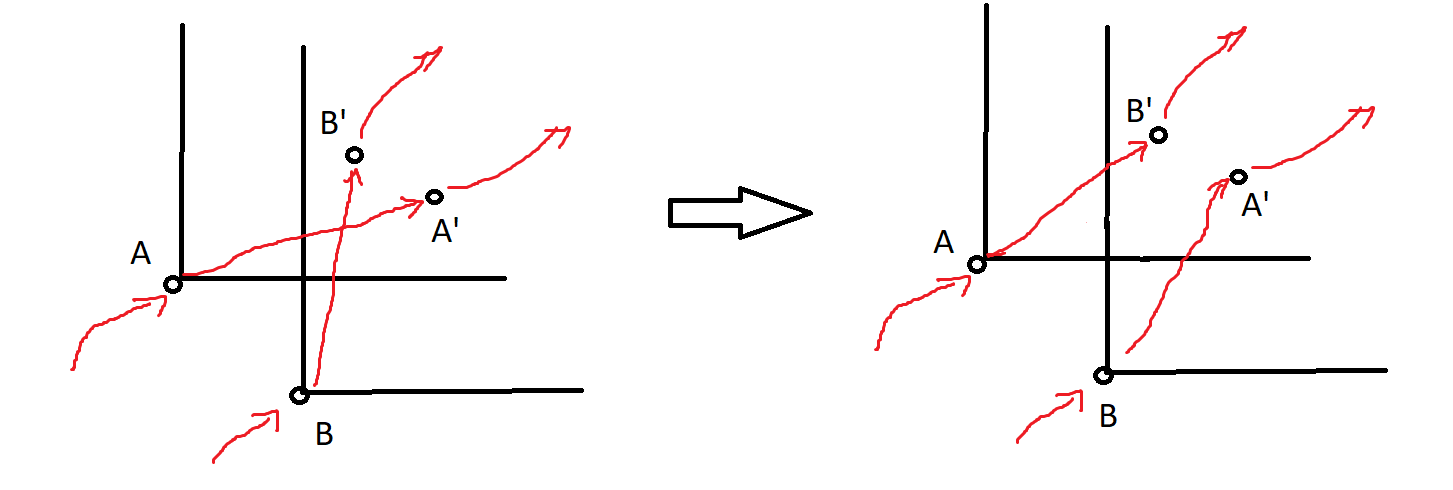

On the image, this corresponds to the fact that it is possible to choose the red paths so that they do not intersect.

Proof:

Let's look at a situation where the paths intersect and let's label the points as in the image. Since the edges and

intersect, the points

and

have to be in the intersection of the 'fields of vision' of the points

and

. Thus, instead of the current edges, we can take the edges

and

, untangling the paths. Using a sequence of such untanglings, we can make it so that the paths do not intersect. □

Since there exists an optimal solution in which the paths do not intersect, the idea comes to mind of trying to pick paths from left to right (it is possible to make a solution in the opposite direction) such that we take the paths that are 'as left as possible' so that we would have more room for the remaining paths. The following claim shows that the right choice is in fact the lexicographically smallest LIS, i.e. that it leaves the most room.

Claim 2:

Assume that from each layer, we have removed a prefix of points, so that only the remaining points are allowed to be used when constructing a LIS. The lexicographically smallest LIS of the remaining points will then be the smallest for each layer separately.

Proof

Assume not. Denote the lexicographically smallest LIS by . By the assumption, there exists a path

such that in the first layer it begins at the same point or later than

, but which finds itself earlier than

in some other layer. The first place where this happens is actually a crossing, which by claim 1, we can untangle, obtaining a lexicographically smaller path than

. □

A consequence of claim 2 is that each point that is to the left of the lexicographically smallest LIS (in any layer) can never be used for building a LIS. Thus, the solution can be obtained if at every step, we choose the lexicographically smallest LIS and remove all of the points on or to the left of it. A solution that goes through all of the remaining points for each step and finds the desired LIS solves the second subtask.

To solve the third subtask, the searching process should be sped up. Say we're trying to build our current LIS and that we are currently at node (the LIS is built in order from smaller to larger values, and we have so far built a prefix of the LIS). By the things mentioned, node

is the leftmost node in the current layer that has the possibility of being extended to a LIS. All of the nodes in the next layer which are to the left of

can immediately be deleted, because if we can't reach them now, we won't be able to reach them in the future. Then, if from

we cannot reach the leftmost node in the next layer (i.e. if that node is below

), then no path from

can continue to the last layer. For that reason, we should remove node

, and the new current vertex will become

's predecessor, from which we repeat the process. Of course, if it is possible to go from

to the leftmost node in the next layer, the path will continue through it.

After we make the division into layers, which can be done with time complexity , the mentioned searching procedure works in

, which is enough for the third subtask.

Comments